Native Plants and Blooms

What do we take? What do we give away?

We’re in the midst of triaging our plants and trying to figure out which ones will be going with us to Oklahoma. We have well over a hundred different plants1 in pots2, and for each one, we need to decide if (1) we like it well enough to transport it, (2) will it survive in a different gardening zone, and (3) is it native, introduced or invasive. Right now, we’re focused on just the flowering plants — the herbs and veggies will come later.

Our goal is that the vast majority of our plants should be native. This isn’t just an aesthetic choice; there are very real reasons why native is the better choice. Here’s the way I understand the differences:

Native Plants — plants that have historically existed in that particular area. In the United States, “historically” generally means since European colonization.

They can survive variations in local weather.

They attract pollinators, beneficial insects, and other invertebrates, which support diverse systems that attract birds and other wildlife.

They enhance natural biodiversity by feeding animals and fungi, and building soil that feeds other plants.

They store carbon dioxide and reduce the need for heavy machinery like lawn mowers, which helps fight climate change.

They tend to retain moisture better than non-native varieties, which can save money, resources, and effort and promote soil health.

They can can tolerate native pests and diseases.

They require lower maintenance than introduced plants.

Non-Native (Introduced) Plants — a species that originated somewhere other than its current location and has been introduced to the area where it now lives (also called exotic species).

They don’t necessarily pose a threat to native plants, but they don’t support the ecosystem as well.

Insects and other wildlife that have co-evolved alongside the native plants are able to not only get the nutrition they need, but are able to survive any defenses the plants may have. Non-natives may not provide the needed nutrition, or worse, contain toxins poisonous to the local wildlife.

They may require more maintenance or care.

Shallow roots and decreased water retention can increase soil erosion.

They can decrease local biodiversity, disrupting a balanced ecosystem that has evolved together over millions of years.

Non-native plants aren’t necessarily bad, but they can be. For example, many people like to have milkweed plants to attract butterflies. Most people just go to big nurseries or box stores to buy their plants, and that’s where they find milkweed. The problem is that most big nurseries sell tropical milkweed, a non-native plant. It’s simple to propagate, allowing growers to rapidly produce the plant for quick sale. The plant is also attractive, both to humans and monarchs, providing flowers and lush green foliage throughout the growing season.

The problem is that native milkweed dies in the winter, and tropical milkweed can last throughout a temperate season. This can either interfere with a monarch’s life cycle, causing it to stay longer instead of migrating, or potentially expose it to a parasitic disease called OE - Ophryocystis elektroscirrha - that can cripple and sometimes kill them. One way OE is transmitted is through milkweed leaves that are eaten by caterpillars. When native milkweeds die back after blooming, the parasite dies along with them so that each summer’s monarch population feeds on fresh, parasite-free foliage. In contrast, tropical milkweed that remains evergreen through winter allows for OE levels to build up on the plant over time, meaning successive generations of monarch caterpillars feeding on the plant can be exposed to dangerous levels of OE.

To combat this, you can either plant only native milkweeds (which can be hard to find), or cut back your tropical milkweed to within 4-6 inches of the ground each October.

Invasive Plants — a non-native species that causes harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health.

They can disrupt the growth or cause the extinction of native plants (as well as the animals that depend on them) and spread quickly.

They can harm both the natural resources in an ecosystem as well as threaten human use of these resources.

They can damage parks, streams, and infrastructure.

They can result in an increased risk of uncontrollable wildfires.

As stewards of the land we’ll be living on, we want to do this right, so we’re taking our time to do some research. One of my favorite websites for finding bird-friendly native plants is the Audubon Native Plant Database. Just type in your zip code and you can get an extensive and searchable list of all the plants that are local to your area, along with local resources and the types of birds that each plant will attract.

If I’m trying to identify a plant (Julie is much better than I am with plants — I’m a bird guy), I use PictureThis, an app that lets you take a photo of a plant with your phone to identify it. It’s not perfect, but it works well enough. It also tells you the distribution ranges for native, introduced and invasive.

While we are concentrating on native species, there are a few non-native plants we want to bring, mostly for sentimental reasons.

For example, this amaryllis has been in my family for over 60 years. It’s been moved from Texas to Virginia to Maine to Georgia to Louisiana and has thrived in every place. My mother got this before I was born, and she’s given bulbs to all her children. I suspect this one will do just fine in Oklahoma.

Of course, being a naturalist, I had to look up the taxonomy, and I discovered that this is actually a hippeastrum, not a true amaryllis. Hippeastrum is a Central and South American native with around 90 species and 600 cultivars in the genus. A true amaryllis, or belladona lily, is from South Africa, and has only two species in the genus.

Both hippeastrum and amaryllis were placed in the same genus in 1753, but after many years of development and confusion, they were officially separated in 1987. Although this decision settled the question of the scientific name of the genus, the common name "amaryllis" continues to be used. Bulbs sold as amaryllis and described as ready to bloom for the holidays belong to the genus Hippeastrum. If you’re a botany geek, it’s a fascinating story. I’ve always called it an amaryllis, and I’m too old to stop now.

One plant down. Many, many more to go.

One plant I know we will definitely NOT take is the japanese honeysuckle growing wild in our yard.

This is another plant from my youth. I can remember plucking blossoms as a child and sucking out the nectar from the bottom. I’ve always had pleasant memories associated with honeysuckle, and it’s only been since I started learning more about plants that I found just how invasive this is.

Japanese honeysuckle was introduced in New York in 1806 for ornamental, erosion control and wildlife uses, and has since spread to the entire eastern United States. It is a fast growing vine that can kill other vegetation by smothering or girdling, and with few natural enemies it can quickly out-compete native plants. It’s classified as a noxious weed in Texas, Illinois, and Virginia, and is banned in Indiana and New Hampshire.

Another plant we won’t be taking is our lantana. Although the bees and butterflies love to visit, it can be toxic to horses and cattle. Probably not the best plant to have on a ranch.

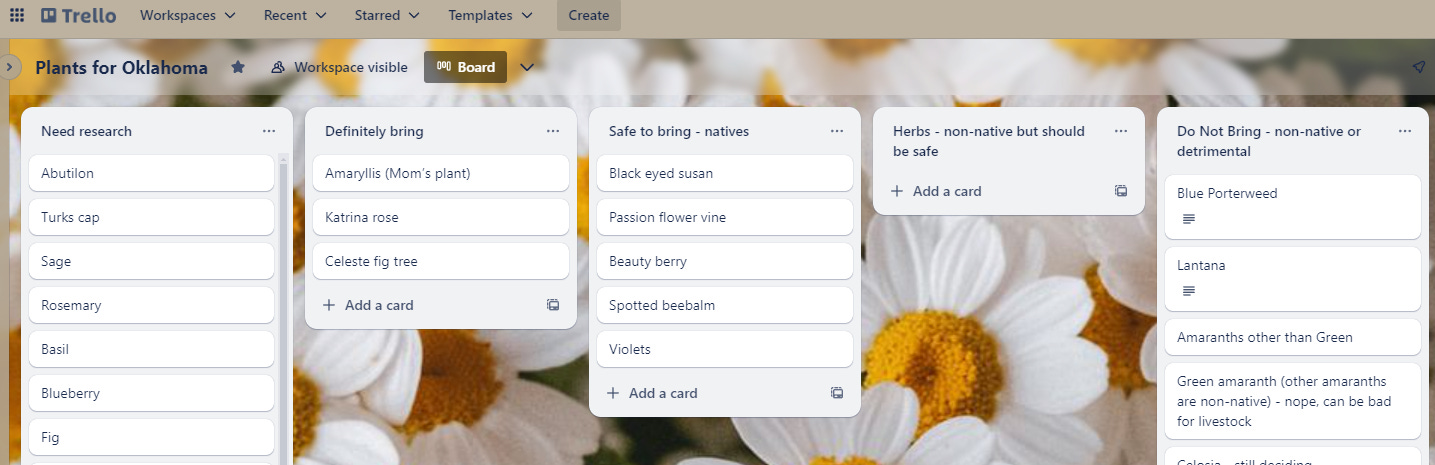

We’ve started a Trello board to help us with organizing this process:

Two of the flowering plants we are bringing:

It’s a long process, but we still have some time. And as we do this, we’re learning more and more about the plants we do have, and what we might want to get once we’re actually there at the ranch.

And, speaking of that, the fence gates are on hand, and I’ll be going up later this month to get the rest of the fencing and start the building. Getting closer!

We used to pull all our plants onto the porch during hurricanes. That got old quick, and now they just fend for themselves.

Julie didn’t believe she had that many, so I counted. Counting the garden tower as one, even though it has several dozen plants, I counted 209.

Oh my goodness, it is a JOB to move with plants! I did it a couple years ago. Lost both of my Korean tea plants, but my plum tree and lavender survived. Good luck to you!

I had no idea about the milkweed! Fascinating. So love reading these. 💜